The Mind’s Artistic Eye

Very recently, the question was posed to me: “Is it harder to paint realistically, or in that style you do?” and I went a little bit into auto-pilot and didn’t really consider all the points to tackle that I should have in answering. In this post I will address the subtler differences between the two terms realism and abstraction, and clarify the sometimes interchangeably used pair representational and non-representational – terms that are often incorrectly used in their place. The conversation had lingered in my mind and I slept on it, and on waking I knew it deserved a better response, so…here I am.

Very recently, the question was posed to me: “Is it harder to paint realistically, or in that style you do?” and I went a little bit into auto-pilot and didn’t really consider all the points to tackle that I should have in answering. In this post I will address the subtler differences between the two terms realism and abstraction, and clarify the sometimes interchangeably used pair representational and non-representational – terms that are often incorrectly used in their place. The conversation had lingered in my mind and I slept on it, and on waking I knew it deserved a better response, so…here I am.

My answer to the question was incomplete. Mostly it was one-sided – how I went about my stylized abstraction, but I did not compare and contrast it to depicting things with more realism. I didn’t really acknowledge anything about realism, and I have to guess that it’s because I still take realism so for granted.

The fact that artists can see in a nearly infinite number of ways can be overwhelming; I understand all too well – I’m in the thick of it. But I can see how it also would be daunting for a non-creative who is observing from the other side of the looking glass. People who have known me for many years have seen me create in a number of styles because I push and change my own way of seeing as I develop as an artist. This diversity of creativity, which happens on the individual as well as the mass scale within the creative community, is what creates a breathing, dynamic culture – so there’s something for everyone.

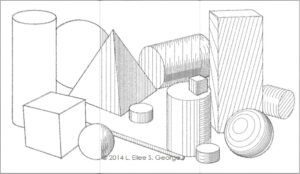

Something that few people already know about me is that, at an early age, I worked and worked myself into being a photorealist. I learned about linear and atmospheric perspective, and observed properties of light and shadow and their effects on colors and textures; I studied in depth anatomy, construction, and the mathematical basis beneath it; I poured over color theory, as well as learning a variety of different media before I concentrated on my favorites. All of this and more gave me a solid foundation for later experimentation: you cannot effectively break the rules without knowing them first. Without that structure, you can’t employ restraint or focus, and without those, all that comes out is meaningless chaos.

That isn’t to suggest that abstracted and non-representational art, those misunderstood stepchildren of the art world, are wantonly chaotic. Frankly, it’s absurd that they are still viewed by a few as far too controversial, in this day and age. But folks often reject what they don’t understand, and many go on the offense by making harsh judgments out of self-defense of a (this is the key word:) curable lack of art knowledge. Learning the difference is really not that painful, and it will enrich your enjoyment of art and design overall.

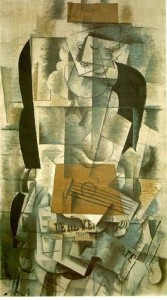

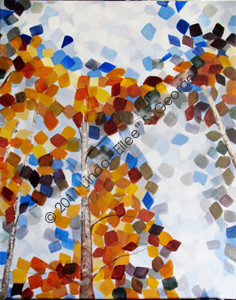

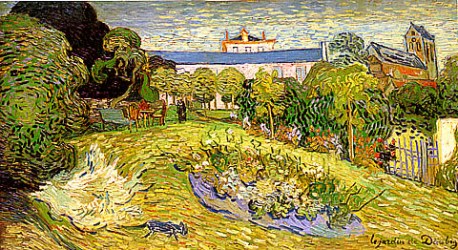

Simply put, representational art looks something like what it’s depicting (to one extent or another), while non-representational art isn’t even meant to particularly look like anything comparable that you can sit and observe. Representational art can be realistic, or abstracted to any number of degrees. Even my abstracted trees are representational, because in my stylized way, I’m still representing something recognizable: trees, sky, ground, mountains – making up landscapes. (Incidentally my paintings are a fusion of realism and abstraction, as I often make the trunks and branches more realistic to give context to those square leaves and backgrounds.) Picasso, who also evolved through many styles, pushed it even further with his Cubist works – Three Musicians, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Guernica most certainly are representational of very specific subject matter – although the exact style he chose in that period included play in pattern, time, space, symbolism and refraction as well as other cerebral expressions – but no one would deem it realistic, because people and events don’t actually look the way he painted them. Using the technique he used – essentially warping the subjects in a particular way – created tension, symbolic movement and emotional impact within the viewer that wouldn’t have happened so effectively in a more realistic style.

“Realistic” describes a style that adheres as closely to how an object actually appears as is possible or practical for the artist to draw or paint or sculpt. Realism is, in one technical use, a term attached to a specific Western art movement at a certain time, in this case it began in France in around the mid 1800’s and spread from there; it was also sometimes called Naturalism, and portrayed scenes of common everyday life. Another example would be Magic Realism, begun after the WWI era (it includes works by Andrew Wyeth and Henri Rousseau), or Surrealism (that includes works by Salvador Dalí and René Magritte.)

These last two movements mentioned used very realistic depiction of what at first seems like everyday scenes, but upon closer inspection, they include increasingly fantastical elements in them. Other types of Realism, like Contemporary Realism, followed. Realism also is used as a more general term used to describe this accurate vision applied in art in many different art periods through history (such as the incredibly realistic way that the human form and its environment were represented in ancient Greece and Rome).

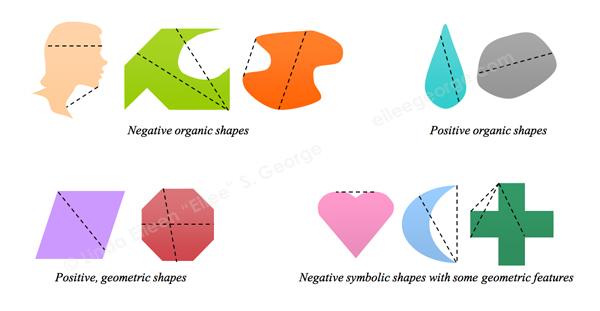

The term that gets most people confused is the word “abstract”. Most people who haven’t devoted studies to art automatically default to thinking that abstract art doesn’t look like anything. But it does, in a way, after running through the filter of an artist’s eye, or concept. You see, when you paint abstract art, the subject is abstracted from something. It’s an abstracted version of a tree, or of a person, or of a landscape, or a still life – it’s still representing something; therefore, it’s representational. People mistakenly brand non-representational art as abstract, and it just ain’t so. It is also worthy to note that there are infinite degrees of abstraction possible, from slight to extreme.

So what is “non-representational” art then? On this there is debate, even within the art world. Some insist that it can represent emotions, symbolizing things with colors and textures of the brushwork, or it can represent cognitive concepts, like when it demonstrates manipulations of chosen elements and principles of design. Hardliners, however, will tell you that it can’t represent anything at all – it’s just art for art’s sake. Well, many artists choose to not draw what they see, but instead what they think and feel, which is interpreting something. When I did my Grief series, I called it hard-core abstraction, but did so rather emotionally. Some would say that since you couldn’t sit down and see an emotion itself (as opposed to how it surfaces in the words and expressions of a human being), that these are nonrepresentational works. But I say in a sense they are representational, in that they evoke a definite feeling and, in essence, represent these stages of grief. Even if you can’t see them in normal life, many people see the feelings when they look at my works. Every time I’ve shown them they elicit passionate reactions. So it must represent something to the viewers, too – and people bring their own life experiences with them when they look at art, and that colors their perception. I can generally tell right away if it’s someone who has lost someone very close to them; they know that feeling – and they recognize it in my work. And, they may bring something different to that painting when viewing it, than I did in making it. Together, we create a complete experience.

What those Grief paintings are, regardless of the non/representational question, is abstract. I have worked in several degrees of abstraction, that series being the far reaches and most abstract – the abstraction of the very intense feelings that I had to either get out or burst. What I had been through recently in real life preceding those five paintings was incredibly difficult, and I suspect I was on the verge of a breakdown, but the art helped me to get the feelings out and process them, and it was better than any therapist would have been (my apologies to therapists, but I’m lucky to have no need of you personally – between faith, a supportive family, and art – really, the bases are covered). Those paintings, which you can view here, are both abstract and, to me and several others, representational – although to others they are also nonrepresentational since you can’t recognize an object or scene. See? There’s gray area even for artists, so if you’re confused have comfort that you’re not alone! (Not to confuse you further, but what these five paintings really are is Expressionistic, but that’s another blog post.)

And my various tree series are also abstract. They are a style that I developed when trying to find my own voice and my own unique eye; I applied a philosophy and related a technique to it. And that brings me back to the question at the beginning of this post:

Is it harder to paint realistically or in that style you do?

The fact of the matter is, after you learn how to draw and paint realistically, it is way easier to work in realism than to stylize and to abstract it. Don’t get me wrong: it was no easy task to learn, for years, the myriad skills demanded in order to depict people, places and things the way they really look – and I have respect for artists who can do that, of course. But that is, quite simply, a skill; I believe just about anyone could learn it given enough time – and there isn’t a lot of individuality to simply regurgitating what’s already laid out in front of you. And these days we have cameras for that…so what can the artist bring to the table, to improve upon that? There are countless answers, and combinations of them. One can assert one’s uniqueness by depicting rather unrealistic things realistically (flying elephants anyone?), which wanders into Magic Realism or Surrealism and is a fat lot of fun. Another way to go is to filter your subject matter through a style. Or, you can make it about the message (which some do brilliantly, but my personal preference is not to get very political in my own art; it’s not in my nature – and knowing yourself is important as an artist). Or an artist may develop a radical technique in his or her medium that rather steals the show from the subject matter. The Impressionists did it with their little brush strokes or with dots of primary and secondary color that only “blend” into tertiary, quaternary and further-blended colors as the viewer steps back from the painting, letting their eyes do the work. My Neo-Pixelism (or Neo-Pointillism as it is sometimes called) is similar to that, except that instead of colors that the viewer’s eye is putting together at a distance, I lead the eye to do that with patterns, shapes and lines.

Essentially, in my Neo-Pixelist paintings, I’m painting two paintings at the same time: the one you see from a distance, with all the blobs and strokes falling together into a recognizable landscape (thanks to the brilliant anatomy of your wonderful eyes), and the second one you see up close, where you fall into an abstract forest of square dibs and dabs and patterns. That isn’t easy. It takes a lot of incessantly oscillating thought and careful planning. It takes concentrated decision making the entire time I execute it. I’m constantly trying to balance out the density of strokes to have a certain desired effect far away, and the desired effects change in different areas of each work. I have taught myself ways to simplify the process, but it remains complex. None of it is there in front of me when I see the landscape it’s based on. It has to be generated by my imagination, and continually controlled and shaped by my will, with no other roadmap. My artistic alchemy pays off by producing a unique, beautiful object with my own personal stamp. It’s something that anyone who calls oneself an artist should strive to achieve: individuality.

Some may say that the technique I apply is “formulaic”, as if it were an insult. The thing is, an artist has a narrow line to walk with style. We are expected to be consistent in style by collectors, gallery owners, art dealers, consultants, critics, auctioneers, and even other artists, although few of us like to be pigeonholed. Stability in style shows maturity as an artist and confidence in one’s abilities; it also makes the art a better risk for investors (if you want to get into the dirty subject of “business” – that’s another way to be “realistic”.) Despite the fact that we owe it to ourselves and the craft to experiment and take chances in many directions, you have to be discriminating and not just show every single thing you do. One could throw the same word, formulaic, at any artist (including the Masters) who developed a consistent style for a time, but there’s a difference between mere gimmick and a well-developed method, and only a discerning eye and questioning mind will learn the difference. Of course, it’s also career suicide to find something that works, and then to never grow beyond it, just to keep making sales (which would eventually fail anyway). A good artist evolves. The art should show a progression. Experimentation may seem a little scary, but it’s not life threatening. You must try new things – and even make mistakes (sometimes lots of them) – in order to grow and to find new exciting successes – plus, you’ll never be bored. And that’s as true for life as it is for art.

So…it’s definitely harder to think for yourself…but the reward is more than worth it.

–Eilee

Master painting images courtesy of the old Ookaboo.com

All other content on this site © 2013-2018/present L. Eilee S. George; all rights reserved.

I’m Eilee George, and I like to write anecdotal and how-to blog posts in several creative areas. A lot of my art lesson posts are collected under the Art menu heading above, but you can find them here, too, along with a lot of other topics. I am a strong believer that ANYONE can draw if they want to learn – it’s a set of skills and principles like anything else. As a prolific writer (although not always online), I prefer to use an unstructured, informal sort of prose as my writing style; thus I chose “prose” over the word “blog” in the menu tab title…but it is essentially a blog. On my own time, I write short stories, essays and lots of poetry and songs. Here, I try to categorize topics by media. The following table of contents will, for now, serve only as a teaser as to what you may be able to look forward to reading later on, if you’re continuing in your creative quest and if I find more time to write; some things may change. If you see a link I’ve already posted it. I’ll throw other unplanned entries in as special events occur. If the presentation gets confusing, shoot me an email

I’m Eilee George, and I like to write anecdotal and how-to blog posts in several creative areas. A lot of my art lesson posts are collected under the Art menu heading above, but you can find them here, too, along with a lot of other topics. I am a strong believer that ANYONE can draw if they want to learn – it’s a set of skills and principles like anything else. As a prolific writer (although not always online), I prefer to use an unstructured, informal sort of prose as my writing style; thus I chose “prose” over the word “blog” in the menu tab title…but it is essentially a blog. On my own time, I write short stories, essays and lots of poetry and songs. Here, I try to categorize topics by media. The following table of contents will, for now, serve only as a teaser as to what you may be able to look forward to reading later on, if you’re continuing in your creative quest and if I find more time to write; some things may change. If you see a link I’ve already posted it. I’ll throw other unplanned entries in as special events occur. If the presentation gets confusing, shoot me an email